Memorising Pi

On January 5th 2016 I set myself a goal to memorise Pi to 100 decimal places. My motivation for this was to learn the [Major Mnemonic System] and it's also a personal challenge. Prior to mid December 2015 I knew the five digits that I had learned at school: 3.14159. This had been sufficient for rough calculations with a calculator (for mental arithmetic I use the approximation of 22/7) and for any accuracy and programming I would use constants provided by the language or software. I had previously looked at the Major system but was unable to apply it due to lack of practice. So in December whilst discussing pi with one of my daughter's friends, she was able to recite 10 decimal places (3.1415926535) which I found to be quite impressive. So in the following weeks I learned the next 5 digits I needed to get up to 10 but without using a particular established method; just repetition. A short while later, at the start of January, I had a discussion with a friend at the Hackspace about memory sports and I decided to learn Major system properly with a well-defined goal: to be able to recite pi up to the 100th decimal place. Once I applied myself to the task I quickly exceeded to 100 digits and by the end of January I was up to 300. I set a further goal to memorise 1000 digits in time for World Pi Day 2016.

My memorisation process is really just an exercise in creative writing! I like to work in groups of 10 digits at a time. Each group is remembered as a sentence of 3 to 5 words and each word encodes perhaps 2 to 5 digits. The sentences are not proper English though; it would be way too difficult to try and find the right words in the Major system. The sentences are just keywords and carry a general meaning as part of my overall story. The theme of my story is a large battle set on a Shell World from a science fiction novel by Iain M Banks. In order to be memorable, the story contains peril, includes all the senses, and has remarkable and bizarre happenings featuring familiar people and objects from my everyday life.

--Michael Erskine (talk) 11:56, 8 February 2016 (UTC)

Major System Software

I found that although there were many online and offline software tools for the Major system, none of them fit nicely with my requirements. I started to work on my own software to find handy mnemonics from the digit sequences. Because the major system is based on pronunciation and not spelling, I started looking into ways of encoding sounds with systems like the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). Again, there are many online resources for phonetics but I wanted to write my own software (as usual!). I had previously worked with speech recognition for the Cheesioid project and the CMU Sphinx software; what I was looking for was a phonetic database of British English words that could be programmatically mapped to number sequences. The CMU Sphinx libraries make use of such a dictionary, known as the CMU Pronouncing Dictionary, which uses the ARPABET ASCII notation for the encoding of phonemes.

Here are the valid ARPABET phonemes with examples: -

// Phoneme Example Translation

// ------- ------- -----------

// AA odd AA D

// AE at AE T

// AH hut HH AH T

// AO ought AO T

// AW cow K AW

// AY hide HH AY D

// B be B IY

// CH cheese CH IY Z

// D dee D IY

// DH thee DH IY

// EH Ed EH D

// ER hurt HH ER T

// EY ate EY T

// F fee F IY

// G green G R IY N

// HH he HH IY

// IH it IH T

// IY eat IY T

// JH gee JH IY

// K key K IY

// L lee L IY

// M me M IY

// N knee N IY

// NG ping P IH NG

// OW oat OW T

// OY toy T OY

// P pee P IY

// R read R IY D

// S sea S IY

// SH she SH IY

// T tea T IY

// TH theta TH EY T AH

// UH hood HH UH D

// UW two T UW

// V vee V IY

// W we W IY

// Y yield Y IY L D

// Z zee Z IY

// ZH seizure S IY ZH ER

APRABET phonemes are modified into "symbols" by adding optional digits to indicate emphasis within the word. The full set of possible ARPABET symbols used by CMU Sphinx dictionaries is provided in the CMU Sphinx downloads as file "cmudict-0.7b.symbols". This is a reasonably small set (84 symbols) and I was quickly able to create the following simple mapping of all possible APRABET symbols to the equivalent major digits by ignoring emphasis, vowels and other elements silent to Major system.

| symbol | major | notes |

|---|---|---|

| AA | vowels not encoded | |

| AA0 | ||

| AA1 | ||

| AA2 | ||

| AE | ||

| AE0 | ||

| AE1 | ||

| AE2 | ||

| AH | ||

| AH0 | ||

| AH1 | ||

| AH2 | ||

| AO | ||

| AO0 | ||

| AO1 | ||

| AO2 | ||

| AW | ||

| AW0 | ||

| AW1 | ||

| AW2 | ||

| AY | ||

| AY0 | ||

| AY1 | ||

| AY2 | ||

| B | 9 | |

| CH | 6 | |

| D | 1 | |

| DH | 1 | |

| EH | ||

| EH0 | ||

| EH1 | ||

| EH2 | ||

| ER | 4 | |

| ER0 | 4 | |

| ER1 | 4 | |

| ER2 | 4 | |

| EY | ||

| EY0 | ||

| EY1 | ||

| EY2 | ||

| F | 8 | |

| G | 7 | |

| HH | ||

| IH | ||

| IH0 | ||

| IH1 | ||

| IH2 | ||

| IY | ||

| IY0 | ||

| IY1 | ||

| IY2 | ||

| JH | 6 | |

| K | 7 | |

| L | 5 | |

| M | 3 | |

| N | 2 | |

| NG | 2 | |

| OW | ||

| OW0 | ||

| OW1 | ||

| OW2 | ||

| OY | ||

| OY0 | ||

| OY1 | ||

| OY2 | ||

| P | 9 | |

| R | 4 | |

| S | 0 | |

| SH | 6 | |

| T | 1 | |

| TH | 1 | |

| UH | ||

| UH0 | ||

| UH1 | ||

| UH2 | ||

| UW | ||

| UW0 | ||

| UW1 | ||

| UW2 | ||

| V | 8 | |

| W | ||

| Y | ||

| Z | 0 | |

| ZH | 6 |

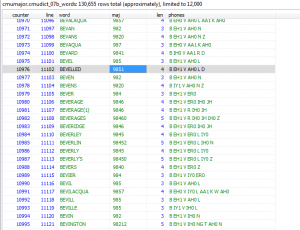

Armed with this table I was able to encode the entire CMU English dictionary (cmudict-0.7b) of some 133000 words to Major system equivalents. I don't know if this has ever been done before but I am happy to share my work! --Michael Erskine (talk) 12:16, 8 February 2016 (UTC)

Database of words

The software reads the CMU Sphinx dictionary in ARPABET format and produces a database table that attaches Major encodings to each word.

CREATE TABLE `cmudict_07b_words` ( `counter` INT(11) NULL DEFAULT NULL, `line` INT(11) NULL DEFAULT NULL, `word` VARCHAR(50) NULL DEFAULT NULL, `maj` VARCHAR(50) NULL DEFAULT NULL, `len` INT(11) NULL DEFAULT NULL, `phones` VARCHAR(100) NULL DEFAULT NULL ) COLLATE='utf8_general_ci' ENGINE=InnoDB;

A database is nice but it is much, much faster to use a local text file and read the whole CMU dictionary into memory. Here's an example of C# code to read the CMU dictionary into a list of objects (one-per-word) that are the same as the database above, with major translations.